Wet Paint by Studio Prokopiou

When paint is dry, it becomes a matte surface. But things can become slippery when wet and in a metaphorical sense, one could argue, this applies to our perspective on art and culture too. Erwin Panofsky, in his influential essay ‘The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline’ (1940),1 questioned art historical matters as “impractical investigations”, yet he deemed them essential “because we are interested in reality” and reality, as we are slowly but surely coming to terms with, is a rather liquid entity. This makes art history a living Thing too, requiring constant tending, updating, and reappraisal to reflect our evolving attitudes.

The field of art history is partial, contentious, and constantly up for debate. One recent matter of dispute has been the issue of polychromy in the sculpture of classical antiquity, concerning the position that classical Greek statues were originally coloured.2 The international and interdisciplinary character of polychromy studies is now firmly established and resulted in exhibitions such as Gods in Color (which toured from 2003-2015)3 and Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color (New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022), both of which served as critical indicators that the academic paradigm in the museum world eventually shifted — be it rather slow, considering the plausibility already expressed by several experts since the nineteenth century.4

The correct observation at the time of excavation of the marble objects was that it was all white, a factual observation of archeologists indeed. But art historians also long assumed that they were once coloured, that pigments on the Greek sculptures had faded following centuries underground, exposure to the elements, and the cleanings they received upon discovery (around the early 1800s). Yet, because those in favour of the polychromy argument relied heavily on close reading of classical texts — not on empirical evidence — it was only with the support of progressive techniques that the art world could fully embrace the notion that the sculpture and architecture of the ancient Greeks was once, in its origins, brightly and elaborately painted.5

Why was this assumption never really made transparent, or communicated to the public at an earlier stage? One theory is that the lack of colour had reduced the sculptures' sensuality and that this coincidentally aligned with the beauty ideals of the Victorian Age. That is, at the time when the museums started to serve as publicly accessible institutions of art preservation, contemporary audiences were admiring the more sterile appearance of the marble and so there was little appetite for adjusting the story that these classical art objects might not always have been unpigmented.

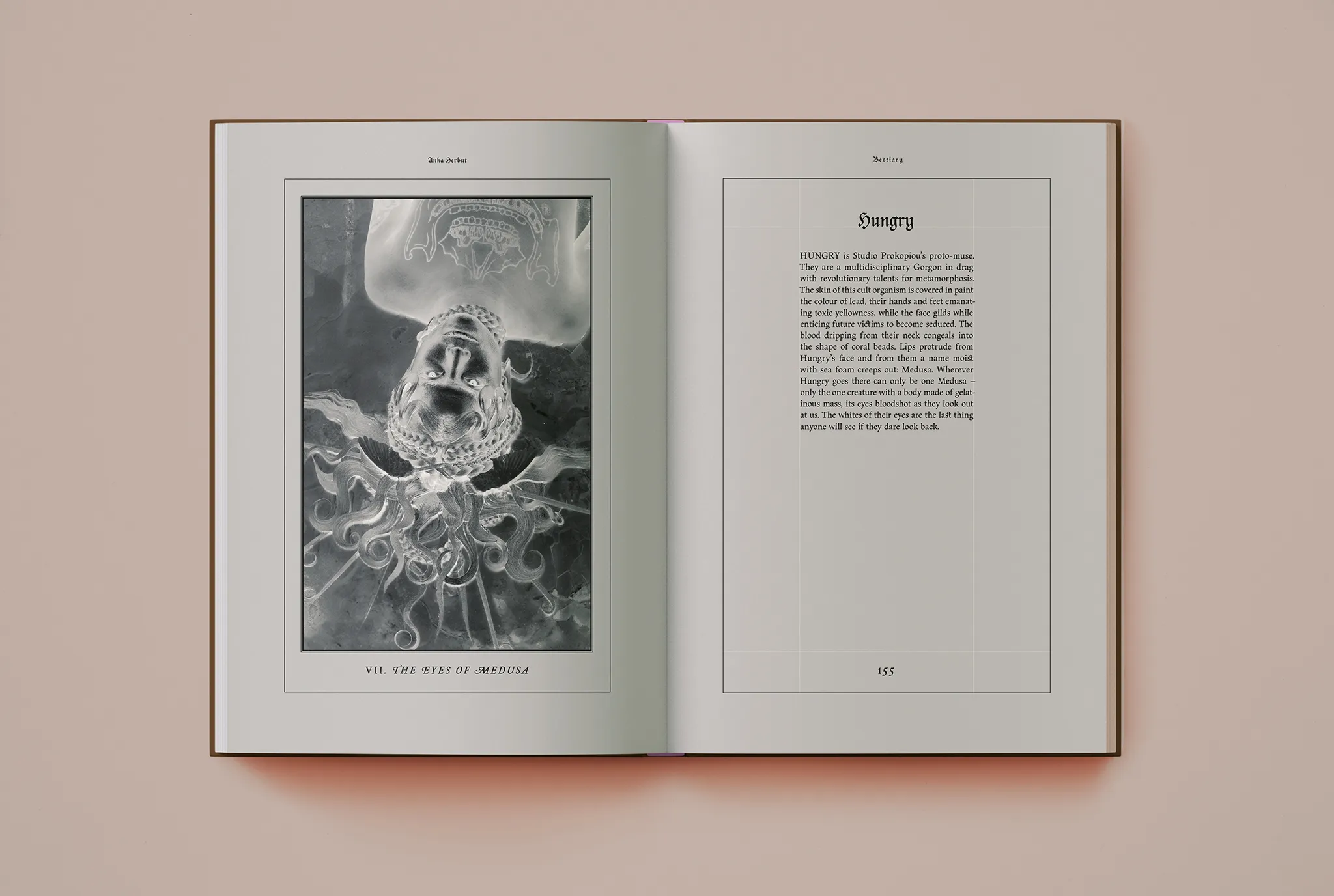

Even today, for many people, the colours are jarring because their tones seem too gaudy or opaque.6 Alluding to this white-or-colour sculpture discourse and the matters of taste to which it correlates, Studio Prokopiou gathered a team of creatives to stage meticulously styled and crafted portraits that hint at ancient Greek sculpture — be it with an aberrant, a postmodern twist. The models were body-painted by makeup artist Luke Harris and details, such as piercings and safety pins, remain clearly visible, while the props, created by co-producer Panos Poimenidis, further stress the queer vibe and the ‘camp-ness’ of it all. This kind of art can be alluring while it almost equally can be insulting to our good taste and its incorporated irony comes with a risk that if one doesn’t get it, all might come across as annoyingly loud; as a visual carnival.7

Wet Paint by Studio Prokopiou, carefully designed by Agata Bartkowiak, has multiple layers and consists of much more than the images that are presented in sections referred to as ‘Plates’, printed on glossy paper and with peculiar titles added to each.8 A ‘Bestiary’ is included, indexing the persons who modelled for the portraits as mythical heroic figures, thus linking the staged portraits to a mythological underworld which, to the understanding of the ancient Greeks, was inhabited by gods and spirits typically associated with death and fertility. The book also contains other creative elements such as drawings, creative writing, and sketches (which indicate the meticulous preparation for the portrait sessions) and this hefty volume, an appropriation of a traditional art catalogue, furthermore has several essayistic contributions by invited authors, altogether giving insightful context to the queer irony as reflected from the images.

The theatrically stylised and quasi-iconoclastic visuals in Wet Paint, embracing irony and impish playfulness, are perhaps not everyone’s cup of tea. The hyper-exaggerated, hyper-realistic imagery merging mythology, pop culture, and BDSM iconography can either come across as aesthetically stimulating or as annoyingly vulgar or plain ‘kitsch’. Either way, this bold and provocative exploration of Greek heritage through the lens of camp aesthetics, blending a formalistic discourse with the vibe of Pop, is not meant to merely support a postmodern pun. It is far from just a simple tongue-in-cheek gimmick and probably best to be understood as both a desire for formal perfection and as a love for the exaggerated, the ‘off’, of things-what-they-are-not.

Wet Paint is concerned with the appropriation and subversion of what for long defined our aesthetic judgements. Elements such as “chipped nails, an orange vagina with a pearl, a statue of a man with a cigarette, a majestic woman as a goddess with a jug on her head”9 are by default camp and can be challenging to the eye, yet it all hints at the liberation of a conservative scope on art history, as a correction of the Victorian moral discourse. Queerness is undeniably expressed here too, but this multifaceted body of work is best considered a humanistic attempt to reach back to Greek culture as a relieving celebration of fluctuating identities, of human instabilities, of “love and devotion as entangled in our sexualities, desires, shame, and fear”.10

The book is complex in its multitude of elements but overall it has a clear scope directing towards an underlying anxiety of humanity about the natural, the unfeigned. Rather than just identity politics, or any sort of statement bringing attention to the marginalisation of people within the difficult-to-categorise spectrum of gender, sexuality, and romantic attraction, its visual content and the argumentations made by the contributing authors suggests how art institutions are to be held accountable for their role in representing culture; how mainstream art histories should offer a more complete picture of humanity, of our manifold complexities; how the ancient Greeks were perhaps living in another time with other social customs and ethics while its people had a range of needs and desires that are just incorporated in our very being.

The museum — concerned with the collection, storage, cataloguing, and display of artefacts through narrativised forms of spectacle to a visiting public — is a discursive space and the artworld concerned with its own traces must adapt to the times and to advancing insights or risk stagnation. In that context, Studio Prokopiou delivers a welcome alternative to a bias that cultivated a thinking of the ancient society as one-dimensional; as merely stoic and emotionally detached, rather than what it most likely was too — colourful, diverse and salacious.11

1 Panofsky, E. "The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline” The Meaning of Humanities, edited by T. Greene. Princeton, New Jersey, 1940, pp. 89-118.

2 Hetherington, K. (2011). Foucault, the Museum and the Diagram. The Sociological Review, 59(3), 457-475. [link] (Original work published 2011)

3 The exhibition Gods in Color has been touring the world in one form or another since 2003 and in 2020 returned to Frankfurt with new findings and reconstructions never before displayed.

4 Talbot, M. (2018, October 22). The myth of whiteness in classical sculpture. The New Yorker. [link]

5 See the 12th International Polychromy Round Table Final Program, which took place in November 2024, and its session: ‘Recent Research in the Greek World’, [link]

6 Idem

7 Sontag, S. (Fall 1964). "Notes on 'Camp'". Partisan Review. 31 (4): 515–530.

8 For example: The Temples, Even When They Survived, Have Passed Into The Invisible World (Plate #3); Even The Gods Must Perish If They Wish To Live. How Could They Hope, Without Dying, To Inherit The Divine? (Plate #10)

9 Wolny-Hamkało, A. "Climax” Wet Paint, edited by Studio Prokopiou. Sun Archive (OPT Zamek), 2024, pp. 237.

10 Idem

11 Nianias, H. "Polychromy” Wet Paint, edited by Studio Prokopiou. Sun Archive (OPT Zamek), 2024, pp. 29-42.